55 Years

MONTICELLO MEDICAL CENTER

1932 – 1987

Hard Times

1932. Failing businesses. Foreclosed mortgages. In Cowlitz County, eggs cost 25ct a dozen, hamburger 15ct a pound. And still people lived onthe edge of hunger as salaries were cut, and cut again.

The press labeled the era The Great Depression. To most local residents, though, it was simply hard times.

Economic woes weren’t the whole story. Longview Daily News headlines for June 20 heralded the firstwoman to fly a plane alone across the Atlantic: “Amelia Earhart Welcomed Home.” A reporter noted a “Big Planter’s Day Festival at Woodland.” Roosevelt and the repeal of Prohibition were the agenda at the Democratic National Convention . The weather forecast was “unsettled. . . probably light rain.”

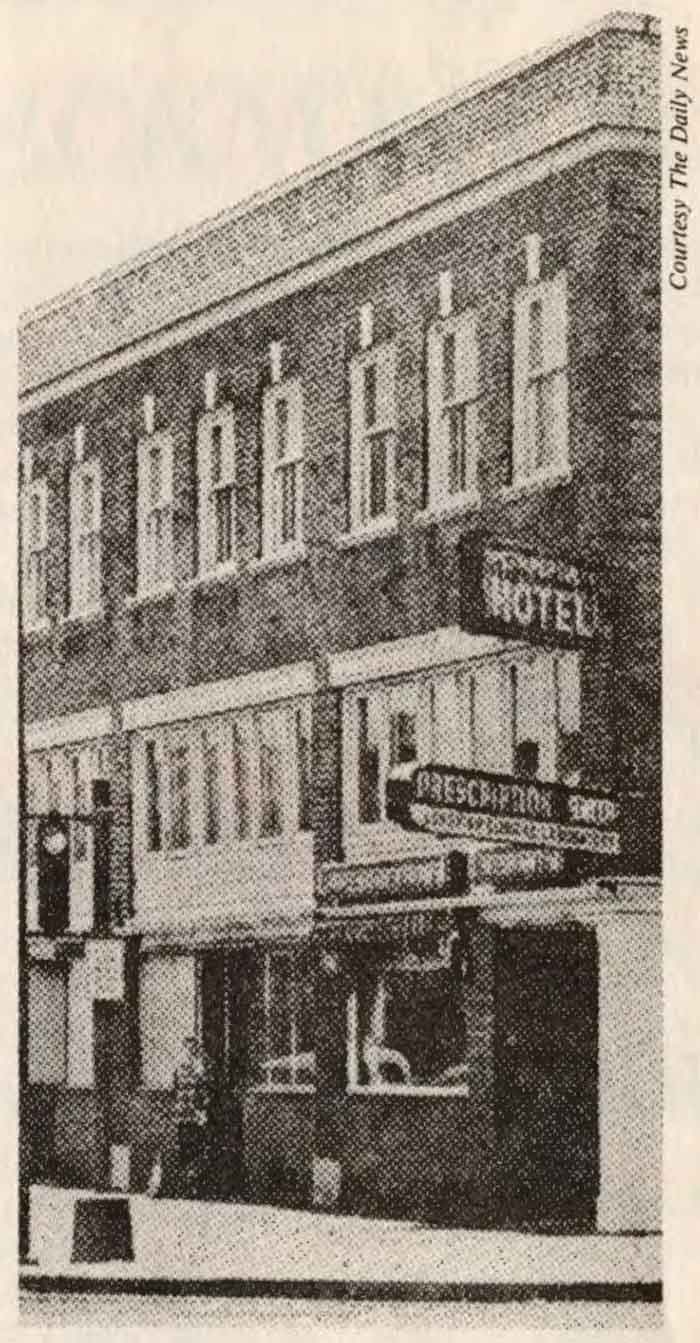

Tucked into a corner of the front page, a brief item headed ” City’s General Hospital Opens” chronicled the beginning of a new business venture. Mrs. Helen Lawrence, assisted by a Miss Gibson, had converted hotel rooms into a twenty bed hospital on the second floor of the Willard Building, 12th and Broadway.

To say the least, a risky venture. But the shaky economy actually produced the need for another Longview medical facility. Kelso General Hospital was private, run by Dr. Frank Davis for his patients. The county hospital took care of the needs of area residents unable to pay for their health care. But Longview Memorial Hospital, begun in 1923 with a gift of land from Long Bell, a sizeable loan, and donations from local citizens and industry, had succumbed to the hard times. Memorial’s Board of Trustees leased it to Drs. Hackett, Coffin and Hayes, who formed the Columbia Clinic. In an effort to put their business on a firm financial footing, the three required all other physicians to guarantee a portion of their patient ‘s fees before using the facilities.

The Commitment Begins

Though somewhat spartan, even for the day, Longview General boasted private rooms in addition to the more usual two and three bed wards. Staff made ” preacher’s seats” with their hands to carry patients up and down the stairs, since there was no elevator. Food for patients and staff alike was cooked on a small home sized stove, but the eleven physicians and surgeons had use of an operating room and handled all types of cases.

To attract patients, the non-clinic doctors soon decided to organize to compete with Columbia Clinic for industry contracts . In an early forerunner of today’s prepaid medicine, they formed the non-profit Cowlitz County Medical Service Bureau. Through the Bureau, an employee could-via payroll deductions-insure himself against potential disaster by paying a fee of $1.00 per month. For another $1.00 for each family member, he could rest in the knowledge that his family’s medical care would be taken care of without additional expense.

When negotiations for hospital privileges with Columbia Clinic proved unsatisfactory, and with community support, the Bureau decided to go into the hospital business. On July 5, 1935, Bureau members purchased Longview General’s assets and opened Cowlitz General Hospital in the Willard Building.

The Bureau’s high standards were immediately apparent. The physicians took particular care in engaging the nursing staff . The surgery was equipped with the best equipment of the time. A search for more adequate quarters was mounted, and in December, 1935, 14 patients were moved into a new 35-bed facility located in the former Longview train depot at the foot of Broadway.

One of the patients making the trip in a York Funeral Home ambulance was Charles Melville, whose back had been broken when he was crushed by sand and gravel in a construction accident. Melville was given medical record number 1 in the new hospital, and became a favorite of the employees during the eight years of his stay. In an era when nurses often handled the switchboard and staffed the emergency and surgery crews-all at the same time-Charlie ‘s help relieving at the phones was gratefully welcomed. When his son Roger was married in 1938 to Evelyn Jones in the hospital lobby, so Melville could attend, employees turned out in their best. Cowlitz General ‘s hospital “family” of close-knit staff was beginning.

The Early Years

The former train depot occupied a particularly auspicious site for a hospital. Situated on thirteen acres of grass and trees, the fireproof brick building was one of four Georgian-style structures given to Longview by city founder RA Long. Extensive renovations and over $12,000 of equipment prepared it for its new function.

The Bureau hired prominent local physician J.W. Henderson in 1936 to manage the hospital and act as medical director of the Bureau. At the same time, Bureau doctors agreed to finance the purchase price of the property and equipment by accepting 25% of their regular fees for Bureau patients in cash, and allowing 75% to be reinvested in the facility. In return, they received debentures, in effect IOU’s with interest from the Bureau, for the amount of their reinvestment. These would be renegotiated several times, ending as bonds held by these early doctors.

The Bureau continued to sign contracts with businesses and industry, and by 1939 had Weyerhaeuser, Washington Gas, M and M Plywood and Longview Stevedore on the rolls, as well as others. Board minutes in 1938 and 1939 reveal that the fee for a home delivery was $45, CGH nurses would get no vacation with pay, and ” no patients of the hospital in wheel chairs should be allowed to go more than one block from the hospital.” Unfortunately, the secretary failed to record the incident which prompted the latter edict.

By March, 1939, Bureau members felt that the hospital was in a strong enough financial position to hire a permanent gardener. Patients crowded the facility and a flu epidemic prompted consideration of “putting emergency beds into the storage room.” Cowlitz General was beginning to outgrow the old station. In 1942, a new 45-bed wing was added, the Bureau doctors guaranteeing a $55,000 loan by taking out life insurance policies.

Cowlitz General Hospital in the former Longview rail passenger station.

WAR!

World War II strained the nation’s resources and siphoned medical personnel out of Cowlitz and Wahkiakum Counties. Costs rose. Workers at Longview’s major industries-unused to inflation, and mistakenly believing that price raises were lining doctor’s pockets-voted down continuation of payroll deductions for pre-paid medical care. Many of the Columbia Clinic’s younger doctors went into the service, forcing the cancellation of the Clinic’s industry contracts, and then closure in 1943.

Cowlitz General absorbed as many patients as it could. Nurses were in such short supply during wartime that the medical staff asked the Girl Reserves to provide babysitting services in an attempt to free more women to work. There wasn’t enough help of any kind. Nurses shoveled sawdust into the furnace and tended the hospital Victory Garden between casting broken bones and more conventional bedside nursing. The hospital ambulance picked up patients who needed care but hadn’t enough of the tightly-rationed gas to get to CGH. The Cowlitz General community sustained a blow · which made the war even more real when 1st Lt. Florence Grewer, R.N., a capable nurse who had held supervisory posts, was killed in the bombing of a hospital ship in 1945.

The failure of the Columbia Clinic caused the building on Kessler Boulevard to revert to the Longview Memorial Hospital Association, who asked a Catholic women’s order to take over. In December, 1943, the Sisters of St. Joseph of Newark (now “of Peace”) opened the newly renamed St. John’s Hospital as an open staff facility available for use by any physician.

As owners of their own hospital, however, the doctors had to make use of it to protect their financial stake represented by the debenture bonds. New physicians, many of whom arrived just after the war ended, wanted to use both hospitals. The Bureau periodically considered selling Cowlitz General. The former passenger depot was crowded and aging, and the physicians were busy, trying to care for the medical needs of an area population which had mushroomed from 40,155 in 1940 to 53,369 by 1950. In some months, the hospital lost money, increasing the Bureau’s indebtedness, and prompting instructions to raise the price of full meals from 40¢ to 50¢, and to “lessen the amount of food on plates.”

In 1950, a U.S. Public Health Service report determined that 112 more hospital beds were needed in the county. Despite the $17,000 worth of remodeling and new equipment the Bureau purchased in the late 1940’s, continued expansion of Cowlitz General would be necessary.

“Cowlitz General is Your Hospital”

Concerned citizens, galvanized by the Health Service report, formed the Inter-Community Memorial Hospital Association in 1951, for the purpose of purchasing Cowlitz General and financing an addition. A crimp was put in their plans when the government reevaluated the county need down to fifty beds and gave St. John’s (as the most efficiently expanded of the two hospitals) $400,000 of federal money to partially finance them. But the seed had been planted for community ownership of CGH, and in March, 1954, Cowlitz General Hospital, Inc.a non-profit citizen group with no financial interest in the hospital-took over the facility. The purchase price of $237,275 {for an estimated $800,000 worth of property and equipment) represented the value of the debenture bonds issued for the uncompensated work early physicians had done for Medical Service Bureau patients. The Bureau members, in effect, gave the hospital and its assets to the community.

Despite 79% occupancy of Cowlitz General’s beds in the mid 1950’s, cash flow continued to be a worry. The Board had no thought of making money by overcharging their neighbors, but medical costs were among the fastest rising of the post war years. In a joint Board and staff meeting with St. John’s in 1956, Cowlitz General Administrator Roy Ecker pointed out that hospital costs nationally rose one per cent per month during the ten years from 1946 to 1956. Reimbursement for welfare patients was slow, and often on a scale several years behind actual costs to the hospital, a fact which forced charges to paying patients to be somewhat higher than actual costs.

The constant leaps in technology which so characterize health care today were just beginning in the 1950’s. Cowlitz General purchased a $12,000 X-ray machine, a new $7,000 image amplifier for sterilizing equipment and a hydraulic patient lift. Reluctantly, the Board found it necessary to increase rates in 1958 to $21.50 per day for a private room, $17.60 for a bed on a ward.

One of the most constructive steps taken during the transition of Cowlitz General to a true community institution was the formation of the Auxiliary in 1957. A strong and active group of women, the Auxilians quickly stirred public interest in the hospital. Their first major project, a Christmas Magic bazaar, raised $500 for redecorating the children’s ward. The bazaar, renamed ” Trifles to Treasures,” and a yearly smorgasbord became fixed events in the local calendar.

Meanwhile, renovation and upkeep of the old train station continued. A $24,050 Ford Foundation grant to CGH went for an elevator upgrade, a new central supply area, a new ceiling sprinkler system, and a complete-though thrifty-redecoration throughout the hospital. Employees knew Cowlitz General didn’t have a fancy building, so they prided themselves on providing a high quality of patient care and cleanliness. The white glove check for dust and culturing what a cotton swab could dig out of the corners of the linen closet (a test for germs) were common practice .

But the best of care could not postpone the inevitable. During the late 1950’s and early 1960’s, State inspectors repeatedly warned Cowlitz

General’s Board that it was time to plan for a new building. The old depot, well built but cramped and lacking the steel reinforcing in the roof required for medical facilities, would have to be replaced. County population had reached an all time high of 57,801 in 1960, and was expected to rise another 15% in the next decade, which meant that hospital useage would also increase.

Board members explored alternatives. There had been little hospital construction nationally since 1955. Many older facilities were crowded and obsolete, and the federal government anticipated substantially increasing its Hill-Harris (Hill-Burton) funds, which covered up to 40% of the cost of construction of local hospital facilities on a matching basis. Longview was near the top of the priority list in Washington State for those monies.

In late 1962, CGH purchased the building from the remaining bond holders and completed a $91,000 addition designed to keep the hospital open until a major fund-raising effort and building campaign could be mounted. Just a year later, the train depot clock tower, 15 feet square and rising 86 feet above the ground, was found to be listing and cracked. Two engineers recommended removing it, and in September the familiar landmark was taken off the hospital building. The break with the past had begun.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Compilation of the history of an institution as complex as a community hospital could not be done without the help of people for whom the events weren’t history, but daily life. Our heartfelt thanks to those who searched their memories and attics for information, particularly Dr. John Nelson, Joseph M. Horner, Dr. Robert L. Pulliam, Jr., Alden Jones, Winnie Ryan, R.N., George Schwartz, and Dr. and Mrs. H.D. Fritz. Thanks, too, to the anonymous individuals who put together the hospital scrapbooks through the years, and to current MMC employees who braved the basement to dig through back records and gather lists and statistics. We regret that space precludes us from mentioning you all.

Grateful acknowledgement must be made of MMC’s fellow long-time county orgariizations who granted access to their records and/or permission to use photos and quotations: the Longview Public Library, The Daily News, Cowlitz Medical SeNice (once “The Bureau” }, and the Cowlitz County Historical Museum. Special thanks to museum director David Freece for his support and advice.

Most of all, thanks to you, the citizens of Cowlitz and Wahkiakum Counties. You gave our work context and meaning, and made our history possible.

Cowlitz General’s first quarters. The building is just east of that now occupied by Kortens.

Roger and Evelyn Melville were married in the Cowlitz General lobbyJune II, 1938.